I'm Getting Sentimental Over You Unsentimentally

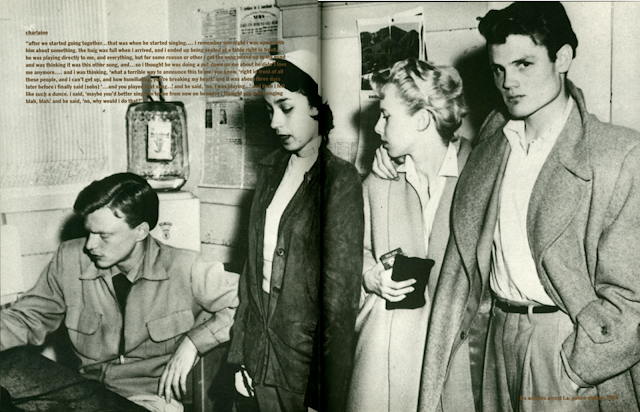

Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker (with two unidentified women)

Ella Fitzgerald’s rendering of I’m Getting Sentimental Over You was a revelation, including the pleasurable shock of hearing the alluring lyrics for the first time because the song is more commonly presented in instrumental form. Rather than skirting around the rasa of the famous music by George Bassman, with lyrics by Ned Washington, Fitzgerald confronts the song directly and irrevocably with a tempo so slow and timbre so tender as to melt snow. Noticing an obvious similarity in shape from their opening melodic utterances, including mood and also titles, one wonders if I'm Getting Sentimental Over You from 1932 was the original inspiration for In a Sentimental Mood from 1935, the latter music by Duke Ellington (and Otto "Toby" Hardwick?) with lyrics by Manny Kurtz and Irving Mills. Complicating possible origins further, the initial seven tones of In a Sentimental Mood are identical to Someone to Watch Over Me from 1926, with music by George Gershwin and lyrics by Ira Gershwin! Given how his songs that became standards, including Stella by Starlight, Invitation, Green Dolphin Street, My Foolish Heart, I'm Getting Sentimental Over You, The Nearness of You and I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You, were central inspirations for the music of seminal jazz artists including Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Miles Davis, Tommy Dorsey, Clifford Brown and others, one would have to partially rewrite the history of jazz without the contributions of lyricist Ned Washington. Same goes for Ira Gershwin, of course, whose output is more famously known. From available evidence I've uncovered, including a pertinent exchange with his granddaughter, and lyrics written for When My Sugar Walks Down the Street and Minnie the Moocher years before he met Duke Ellington, I would include Irving Mills, who was born Isadore Minsky, in the same rarefied category. There are unusually complicated controversies related to the overlapping careers of Mills (he was also a brilliantly innovative figure in the promotion, presentation and selling of music) that are beyond the scope of this writing, yet Duke Ellington himself confirmed that Irving Mills was the lyricist for his songs. Most interestingly, the son of Irving Mills, Bob Mills, writes: "In spite of a limited vocabulary Irving had a poetic sense of beauty and knew how to create a lyric, sometimes using a ghost writer to complete his idea, and sometimes building on the idea of the ghost writer. It was 2003, and not having seen Lee Konitz in nearly three years, I was anxious to see how his health was having heard about bypass surgery he had undergone subsequent to our last series of hanging out sessions in 2000. Like an Olympian gold medalist proudly holding his trophy, Lee immerged from the crowd of people getting off the plane with his alto saxophone swinging from one arm, seemingly stronger than ever. Eager to share some new recordings recently enjoyed, I played a cassette recording of the extraordinary performance mentioned above while we drove to Lee's hotel, which features simply and elegantly the pure voice of Ella Fitzgerald accompanied by the solo piano of Paul Smith. "It’s too sentimental!" Lee exclaimed while scrutinizing the kaleidoscopic urban landscapes along La Cienega Boulevard from the passenger seat next to me, and I was stunned because this great artist had absolutely missed the point. There is a marked if subtle distinction between the maudlin and the rawly naked power of direct, unembellished sentiment delivered with spiritual authenticity, the latter being quintessentially appropriate in the context of Ella’s interpretation. My feeling about Ella's interpretation of I'm Getting Sentimental Over You was absolutely confirmed when later hearing Frank Sinatra, the jazz artist Lee listened to for inspiration, using a nearly identical slow tempo and sentiment for the song. Konitz’s objection was to one track and not Ella Fitgerald’s singing in general, of course, even though both Lee and myself believe Sinatra is the greatest jazz vocalist as did Art Blakey, Count Basie, Lester Young, Lou Levy, Stan Getz and myriad others. Echoing what I believe to be a similar misunderstanding a day or so later during our 2003 hanging out sessions, Konitz, out of the blue, brought up his objection to those who described Chet Baker as being a musical genius. Lee granted that his friend and colleague had been an excellent trumpet player, but was certainly not a creative force on the level of a Lester Young or a Charlie Parker. Let me make this clear: Lee Konitz is easily as great a jazz artist as Young, Parker, or anyone else. However, I have not too infrequently found myself disagreeing with his aesthetic vantage points concerning other musicians and specific recordings. Chet Baker is my favorite jazz trumpeter after Dizzy Gillespie, along with Donald Byrd. Baker’s innovations have more to do with rasa (expression) than anything else, and this is the essence that I feel Lee overlooked: Chet Baker is a genius of musical expressiveness. Delivering his innovative and highly influential range of personal expressive temperaments, ranging from melancholy to celebratory, Chet Baker deployed chiseled, breathtaking assemblages of phrasings, tone colors, dynamics, articulations, pacings, structural flows, and dramatic anticipations that simultaneously coalesced to inform his exquisitely original and inventive melodies and rhythms. And Baker always projected this preponderance of vital musical elements for the purpose of expression as opposed to bare technique. There are few other jazz artists who touch so directly our heart chakras, and such epiphanic moments are sometimes more aesthetically valuable than flurries of even the most inventive and complex musical excitements. If I was asked to produce one improvisation by a jazz artist that sums up the beauty and tragedy of this world we inhabit, Chet Baker’s solo on the title cut of Jim Hall’s Concierto album, heard in the context of listening to the entire track - original concept by Gil Evans and Miles Davis - would be a stellar choice by starlight, moonlight or sunlight. And when you go to listen, keep in mind the same stratosphere contributions of Jim Hall, Paul Desmond, Roland Hanna, Ron Carter and Steve Gadd! But Chet Baker remains the pinnacle of an important jazz vision of life, as does Ella Fitzgerald in all her magnificent glory, and Lee Konitz, too, with his own staggeringly byzantine and finespun methodologies. And without myriad key lyricists together with their more commonly credited collaborative song composers, jazz as we have known it would simply not exist. Come to think of it, together with Louis Armstrong, there is no one who better illustrates how great jazz artists are intimate with the lyrics of the songs they improvise on than Chet Baker because of the way he enjoyed both singing the original melodies of jazz standards followed by improvising upon them with his trumpet, sometimes reversing the sequence. - Michael Robinson, August 2015, Los Angeles

© 2015 Michael Robinson All rights reserved

I'm Getting Sentimental Over You There Will Never Be Another You

Michael Robinson is a Los Angeles-based composer, programmer, pianist and musicologist. His 199 albums include 152 albums for meruvina and 47 albums of piano improvisations. Robinson has been a lecturer at UCLA, Bard College and California State University Long Beach and Dominguez Hills

|