"An artist shoots in the dark, not knowing whether he hits or what he hits." - Gustav Mahler

"That man was very wise." - Pandit Jasraj in response to Mahler

Raga Puriya Dhanashri is the musical personification of India. Remote and inaccessible to the uninitiated, it showers worlds of sublime meaning upon the devotee. The difficulty newcomers have listening to Puriya Dhanashri stems from its unusual combination of swaras, plus an elusive rasa. For myself, it took at least five years after first encountering the raga’s baffling melismas before I felt ready to embark upon my own personal journey within its labyrinthine depths.

While examining the forbidding melodic structure of Puriya Dhanashri, I was astonished to uncover Raga Durga rising from one half-step below Sa and Pa. This creates a provocative, and mystifying friction: Two tonalities a half-step apart! That is, with D as Sa, the ascent and descent of the raga's basic melodic structure is: C# - D# - F# - G# -A# - C# - D# - D - C# - A# - A - G# - F# - D# - D. If you only use the sharped notes from C# up to C# an octave higher, and move back down using the same swaras, we have the melodic structure of Raga Durga, traditionally performed in the late evening. Puriya Dhanashri is a sunset or twilight raga, generally performed just after sunset in the early evening.

As is often the case, it was a recording by Shivkumar Sharma and Zakir Hussain that communicated the essence of Puriya Dhanashri for me, and provided me with the inspiration to develop my own interpretation.

My personal vision of the raga's alap, jor and jhala is more playful and gentle than I have heard elsewhere. This opening section of my non-traditional music expresses adbhuta, and some karuna, for the mysteries, and uncertainties of life. At the same time, there is a feeling of playful shringara rasa.

Upon reflection, I realized that my composition actually began with the selection of the melody instrument, together with the equally important percussion instruments. I chose the clarinet because its timbre and personality seemed perfect for the mysterious and sensual aspects of the raga. The clarinet has a glorious place in jazz history, including Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman, who both had a profound influence on modern jazz alto saxophonists. Buddy DiFranco is a brilliant modern jazz clarinetist. Twentieth-century composers, including Debussy, Poulenc and Stravinsky, wrote some profoundly beautiful compositions for the licorice stick. Stravinsky's "Three Pieces for Solo Clarinet" is one of my favorite compositions. In view of all that history, it was exciting for me to take the timbre of the clarinet to new regions.

Puriya Dhanashri commences the alap with a single tanpura pattern, and the solo clarinet presenting the swaras of the raga. I take special pleasure in presenting a Western instrument with Indian tunings, one of the glorious capabilities of the meruvina, not to mention taking the clarinet well into the bass clarinet register. Added to the exotic tuning, and range expansion, I have cloaked the clarinet with the shimmering cascades of a rainstick.

The jor begins with the steady pulse of a clarinet doppelganger paving the way for the richly woven tapestries of the solo clarinet. About five minutes into the jor, five repetitions of Puriya Dhanashri's swaras are presented in the form of wide-ranging glissandos articulated first by the Japanese kane, and later by the African kalimba.

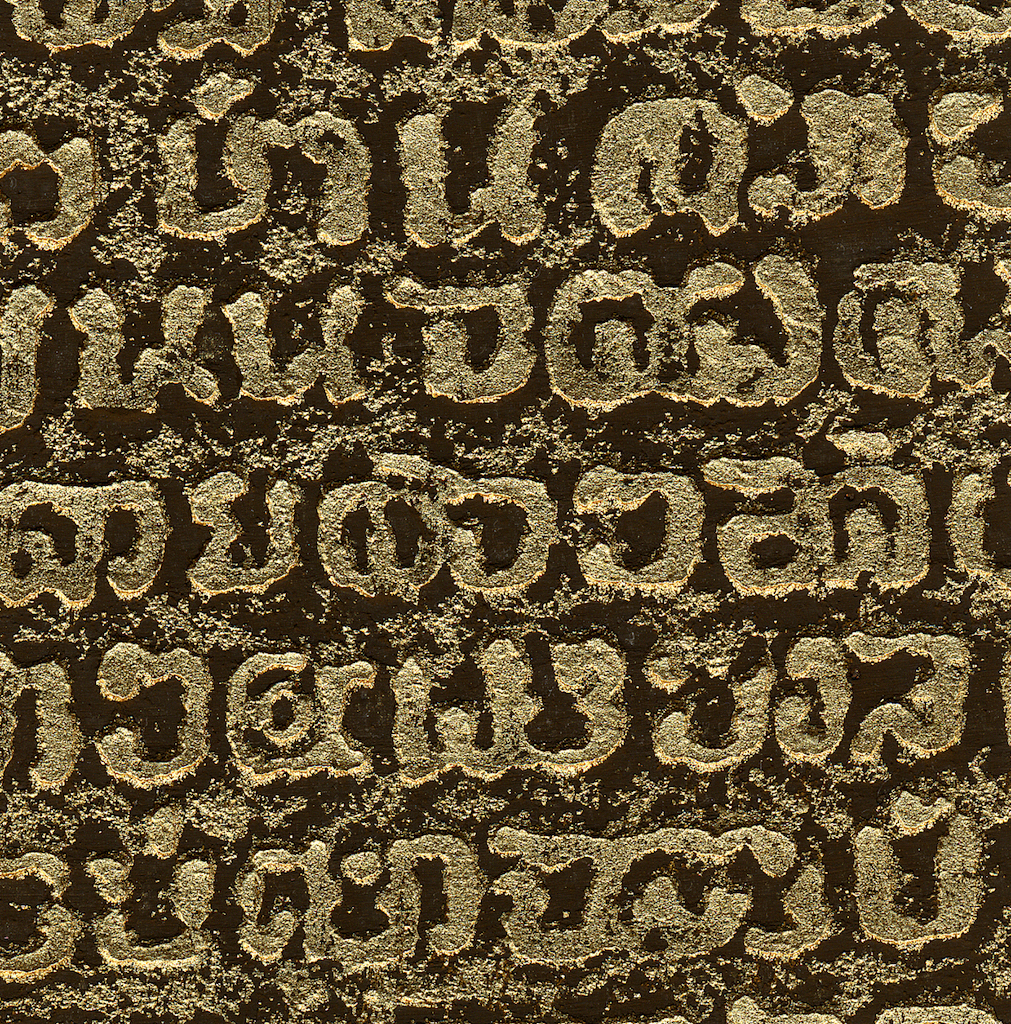

After completing Puriya Dhanashri, I visited a book store searching for poetry to place on the tray card. The poem I found is a spine-tingling homage to Shiva, the Destroyer of Ignorance, and to some, the Progenitor of the Universe. It turns out that the five repetitions of the glissando have an extra-musical meaning because the number five is traditionally symbolic of Shiva's omnipotence. This imagery is reinforced by the raw power of the cover art I selected.

The jhala delights in cascades, peaks and valleys, and propels us into a world of skin percussion timbres. From India, we have tabla, dholak and dhol forming one percussion family. The second family of skin percussion includes the wadon, bebarongan and pelegongan from Indonesiz, the Chinese tang gu and shu gu, the Japanese wadaiko and shimedaiko, and the Korean buk and changgo. This kaleidoscopic commingling of contrasting yet related drums is on one dimension a textural pulsation rendered at a medium slow tempo. A comparison with the paintings of Jackson Pollack spring to mind, with lyrical impulses emerging from the musical canvas. While listening in this manner has its own rewards, I also highly recommend following each musical detail as closely as you would a piano improvisation by Lennie Tristano, or a tabla solo by Swapan Chaudhuri, for the essence of my music is found in the way it evolves and develops.

When the clarinet reappears, we are tossed into a wild, uninhibited dance of melody and rhythm, moving at a fast tempo. There is an otherworldly feeling of exultation and freedom, together with a surrealistic sensation at hearing the clarinet in a boldly new setting. In contrast to the previous section, all of the percussion voices do not appear together. First, it is the Indian percussion’s turn to frolic with the licorice stick, followed by the second percussion family. The section culminates with call and response episodes initiated by the percussion families, and answered by the clarinet.

The final section of Puriya Dhanashri feature the two percussion families palying together again, reflecting the South Indian vision of the raga form, which ends with percussion music. The drums move at a furious pace, spinning off into the stratosphere, and this time, the effect calls to mind one of Jackson Pollack's giant canvases. Rapid drumming forms are called rela in Hindustani music, meaning "rushing," "assault," or "torrent of rain." As in the previous sections of my composition, phrases and divisions of five, seven, nine, and eleven, abound in myriad permutations.

It was a creative challenge to program both the subtleties, and the musical explosions of this piece, working to achieve the effect of a spontaneous outpouring. This was also a challenge of concentration and endurance for me.

Now, I wonder which raga I will turn my attention to next?

- Michael Robinson, February 2002, Beverly Hills