Interviews with Indian Masters

Finding Nazir: The Precious Generosity of Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy

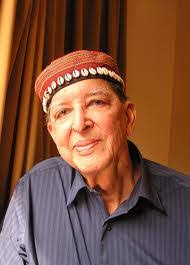

Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy

Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy and myself were standing on the driveway of his home in Valley Village well past midnight, saying goodbye as I prepared to drive home across Coldwater Canyon. It was summertime in Southern California, and the evening sky was especially clear, shimmering with an amalgam of stars, while playfully intermittent, warm breezes shook the adjacent trees to animated life. For the first and only time in our friendship, quite unexpectedly, Nazir embraced me with a giant hug, exclaiming at the dazzling manifestations of nature we were all remarking upon: "Its so beautiful, Michael!" While it was a great privilege to study privately with Harihar Rao, the senior disciple of Ravi Shankar, it also became clear that I would have to consult with other experts in order to begin to get a handle on the vast body of music and knowledge known as Indian classical music. The very name, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, sounded mysterious and intimidating, an impression that was enhanced when Harihar advised me that I was unlikely to meet him at a Music Circle Concert, as if attending such a performance was beneath his lofty stature and experience. My quest for additional teachers was set into motion when Harihar shied away from my questions about the metaphysical properties of ragas I had read about, apparently feeling it was improper to discuss such things with an outsider. Instead, he suggested I contact a professor of Indian classical music at UCLA who was about to become the Dean of Arts and Architecture, followed by assuming the office of Vice Chancellor. The administrator answered my letter with a disappointing response, stating he was too busy to meet with me in the near future. However, fortune intervened when I happened to catch him on a local evening news show discussing some matter related to a priceless violin that had been stolen and recovered. With his image fixed in my mind, I recognized the administrator a few weeks or so afterwards during intermission at a concert by L. Subramaniam at a Westwood, California concert hall and introduced myself. He then, in turn, introduced me to Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy's wife who was standing nearby, and was invited me to the next Friday evening party at the Jairazbhoy home. Parking my car across from the given address that very Friday evening, it was puzzling to me that an exalted UCLA professor of international renown was living in a modest neighborhood in a modest home. But outward appearances would prove to be deceptive as their home proved to exude cultural and intellectual elements which dazzled both night and day. Armed with my most recent recording, Hamoa, I rang the doorbell, and was ushered past the kaleidoscopic rush of Indian artifacts that informed the living room into the elongated and cozy kitchen where sat the aristocratically contemplative great man, his creative intellect silently and effortlessly filling the space. Nazir wore a colorful Indian headdress decorated with seashells, the style of which was charmingly new and exotic for me. At this moment, I also realized I had been the first to arrive for the party, and found myself favored with Nazir's undivided attention. Noticing the CD in my hand, he asked his wife to play it, but she hesitated, perhaps concerned that Nazir would not enjoy the music, and our first meeting would be unpleasant. With some impatience, Nazir insisted upon hearing the recording immediately, and, fortunately, Jairazbhoy was clearly intrigued by the sounds, even if he was puzzled when I said the composition, Water Stones, was inspired by Raga Jaijaivanti, even though the actual swaras (tones) used were from Raga Bhairava or Mela Mayamalavagaula. Nazir was surprised to learn how it was the rasa of Raga Jaijaivanti, as performed by Robindro Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha, which had inspired me to compose my first piece using a semblance of raga form, and how that first-time experience of perceiving the expressive essence of a raga, a quality defined as rasa, had transcended whatever raga I subsequently used for my composition, Water Stones. Apparently, this was the first time Nazir had heard of such a conception, and my tendency to explore new musical paths became central to Jairazbhoy's interest in myself and my music. It was those initial few years of our friendship that became the highlight of our shared time together. I became a favorite of Nazir at the Friday evening parties. He seemed to eagerly await my arrival, and held back nothing in response to my many questions about myriad aspects of Indian classical music and culture, including the legendary metaphysical properties of ragas that Harihar had originally rebuffed. One such evening, Nazir excitedly showed me his brilliant and gorgeous raga diagrams, reminiscent of Kandinsky paintings that are geometric and primal at once, and urged me to compose a composition based upon his descriptive illustration of Kedara. My first two attempts were met with corrections, and each time I decided to start anew with entirely new efforts, with the third attempt meeting his absolute approval. In fact, Nazir (computer spellcheck invariably corrects his name to Nazi) felt so highly about October Sky that he played a recording of it now on the INDIAN JASMINE album for the All India Music Conference in New Delhi that year, along with several other compositions of mine. Unfortunately, Nazir's raga diagrams, which are easily among the most precious and profound accomplishments in the history of Indian classical music study, have not yet been published. I very much hope there are plans to do so because their excitingly original creativity amounts to a treasure trove of sublime beauty and insider knowledge that will benefit many. While Harihar had hesitated to elaborate upon the melodic aspects of raga (in addition to his reticence for discussing their metaphysical properties), feeling uncomfortable with someone who was not studying a conventional instrument, such as sitar, Nazir enthusiastically commenced an ongoing discourse between us pertaining to the dazzling realm of melodic practice and theory found in ragas. His personality exuded capacious generosity, refreshingly authentic warmth of character, intellectual brilliance conveyed with a most refined articulation spoken in pleasingly golden tones, lack of pretense, and a witty sense of humor. Our relationship flourished so much that after having known them for less than two years, Nazir invited me to housesit when leaving on his customary three-month yearly visit to India, beginning in late November. Nazir even insisted I drive his rather fancy car during my stay! Thus began my stay in what Eleanor Academia termed "The House of Knowledge", bedecked with thousands of books and recordings, and decorated to the extent that one felt transported to India upon stepping across the doorway. It was here that I composed my first full-length compositions using elements of raga form, Lunar Mansions and Luminous Realms, deliberately challenging myself by using the most difficultly abstract ragas I knew of at the time, Lalit and Marwa, respectively.

Nazir solved the problem of where to locate my studio by generously suggesting I set-up on nothing less than their splendid dining room table, protecting the exquisite antique wood with a specially fitted glass surface. For my actual composing there was a historically rich and provocative desk with dark wood in a handsome nook of the ornamented living room. Ceilings in the living room were so high it made sense that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had actually been a previous owner of the home.

Michael Robinson in his studio moved to the dining room of Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy and Amy Catlin, including instruments and art from their private collection My life those three months was quite wild, outside of the many hours spent composing, which were absolutely wild too, if in the interior realm of my imagination. This included driving to a large outdoor heated pool with a hot tub surrounded by pine trees in the Hollywood Hills most evenings, accessed with a passcard given to me by a friend. It was delightful to dive in, the steam ascending in hypnotically slow patterns over the enveloping warm water before vanishing into the chilled air. Forty to fifty degrees at night is what stands for cold in Los Angeles! And, after returning back to Valley Village for a shower, I would take the highway the band America sang about in their song, Ventura Highway, in the opposite direction from the ocean towards Chinatown. There, I had discovered a late night restaurant that served splendid delicacies, including mind-blowing Chinese pastries. This superb establishment stayed open to 3 AM, and I managed to arrive just before closing, followed by bringing the culinary bounty home to enjoy. It also became customary to partake of the Nazir's Bombay Sapphire enhanced by squeezing in the juice of freshly picked oranges and lemons from the backyard garden. There was a congregation of fiercely beautiful feral felines who called this garden home and it was my charge to feed them while doing my best not to get clawed during the ritual of their eating frenzies. Speaking of the song, Ventura Highway, there is a tenuous connection with Nazir. As shown below, the song opens with a reference to "Joe": Chewing on a piece of grass There's a hilarious story about how Nazir was being interviewed on radio, and upon meeting the host prior to going on air, it was explained how the correct way to pronounce Nazir's name was to rhyme it with "brassiere". Finding this both confusing and humorous, the host, Mario Casetta, quipped: "Why don't you just call yourself "Joe"?" It was really my ping pong playing that made a favorable impression on Nazir. Outside of an unsettling experience at Tanglewood, where I encountered players from China who did not allow me to make a single shot that even approached the net, let alone go over the net (each time I attempted a return the ball would go instantly sideways due to the extraordinarily wicked spins they deployed), I had defeated everyone else encountered across the table in my "ping pong career", including - brace yourself - a dorm champion at Stony Brook. Ray Krieger, my father's best friend, had effectively taught ping pong to me as a child. Ray was also the person who insisted that I take piano lessons with his teacher, Barney Bragin, who he raved about. Piano lessons with Bragin, while a teenager, became nothing less than the impetus and foundation for my becoming a composer, including the Bach, music theory, and Dave Brubeck with Paul Desmond, Joe Benjamin and Joe Morello jazz he introduced me to, this being the finest Dave Brubeck Quartet by far with the greatest Dave Brubeck Quartet album by far, Jazz Impressions of Eurasia. Nazir had a ping pong table on the patio in the backyard, and it was a central theme of the Friday evening party ritual for people to engage with each other over the table. In short, I was surprisingly much better than anyone else who played and it became necessary to begin using my left hand, which equaled things out a bit. It was clear that Nazir had been a very fine player when he was younger, and he enjoyed watching and playing against me, with my skill at the game seeming to enhance his appreciation for my music, no doubt making some connections with the physicality, rhythm and force of it all. During one of our many discussions across his beloved kitchen table, the walls decorated with his original drawings and paintings, and the air filled with captivating aromas from the freshly ground spices Nazir cooked with, he disclosed, quite poignantly, how during his earlier years, away from home, he had been bullied and subjected to some hideous form of racism, and how a person who turned out to be Jewish had rescued him in quite heroic fashion. For this reason, Nazir felt a special warmth and instinct to assist and nurture those he met who happened to be of Jewish descent, like myself. One memorable Friday evening, Nazir held forth surrounded by a circle of adoring students in his studio (this was an addition to the house, including large one-way glass windows), all hanging spellbound by his brilliantly colorful and erudite oratory expositions pertaining to the Hindu concept of reincarnation, filled with esoteric and riveting allusions to abstract notions of time and space inhabited by unconsciously detached and transitioning souls, all portrayed in excitingly vivid fashion. It was rather fantastic because using only his elegantly dignified and musically cashmere spoken voice, together with naturally subtle facial and body gestures, the effect on listeners, including myself, was comparable to the most extraordinary scenes from the classic film Fantasia by Walt Disney in terms of sheer beauty and wonderment, if on a more intellectual and spiritual plane. These weekly get-togethers were often extremely stimulating, being packed full of interesting people from diverse backgrounds and distant lands, all feasting together on Indian food and drink. One night, Nazir advised me that life began with Scotch, and then proceeded to pour me a glass from his favorite bottle. (More recently, my preference became Cognac rather than Scotch, but I hardly drink at all.) When I learned that Nazir would be returning from India earlier than expected, it necessitated rushing early in the morning to the nearest Seven Eleven on Victory Boulevard in order to replace the beer I had consumed to accompany the Chinese dinners. After entering the store, I couldn't believe how long the line was at that early hour, and was simultaneously amused and embarrassed to realize that the other patrons were sadly viewing me as an extremely pathetic alcoholic who required cases of beer even before breakfast! A most favorite memory is the time I played the brand new Chinese Legend CD for Nazir and other assembled guests. During a particularly surprising and robust sitar passage from the title composition, Nazir exclaimed in loud voice: "Bravo, Michael!" And when a kaleidoscope of disembodied Brazilian cuicas appeared unexpectedly in another episode (an orchestration also found in my three most recent compositions, Lucknow Shimmer, Hummingbird Canyon and The Spirit Pool), Jairazbhoy turned to me with delighted astonishment flashing in his widely opened eyes, experiencing Adbhuta Rasa. Several months before, as was his custom, Nazir began improvising on the sitar for guests towards the end of a soiree, and on this evening his playing was unusually inspired. Then, stopping abruptly, with tears wetting his cheeks, Nazir exclaimed: "I love her so much!" Driving home through the winding, rustic glories of Coldwater Canyon in the early morning hours following that performance, the primary melodic figure for what became my composition, Chinese Legend, floated down from the moon-shimmering trees through the open sunroof into my being, and I completed the new piece in the following weeks. Jairazbhoy also related how he took particular pleasure in the way I combined melodic and rhythmic elements, marveling at the lilas or musical play I engaged in. On an autumn afternoon prior to his leaving for India, I was introduced me to a friendly neighbor who lived directly across the street who was the daughter of parents from India who had lived in South Africa. This elegant, kindly woman appreciated knowing who would be her temporary neighbor for several months. During our conversation, I learned how her father was a lawyer, and their Sunday evening dinners invariably included a particular colleague of his every week, a slight and soft-spoken gentleman by the name of Mahatma Gandhi. During a conversation with Nazir about jazz, I was overjoyed to learn that his favorite jazz artist of all time was Lee Konitz, who I had studied with, and subsequently became good friends with. This preference of Nazir supports my belief that Konitz is the jazz artist closest in musical personality to Indian classical music, despite the fact that he seldom if ever engages in modal improvisation. The connection has much to do with the complexly shaped melodic lines he improvises, and an abstract, mysterious expressive nature. When I shared my insight with Lee, including using the words "varna" and "vakra", Sanskrit terms describing melodic movement in ragas (amusingly, there is an street near Nazir's home with a similar name), with "vakra" denoting multi-directional or crooked characteristics, Konitz, without missing a beat, retorted with a friendly smirk while ironically using a double entendre as smoothly as he famously employs enharmonic tones: "That's right - I'm very crooked" - agreeing with my musical analogy. It was a great joy to introduce my two teachers, Lee and Nazir, in the green room of the Jazz Bakery in Culver City in 1998, following a performance Konitz gave. They scrutinized each other with mutual respect, as I noted how they were born the same year of 1927, with birth dates reversed, Lee being October 13 and Nazir being October 31, which is Halloween in the Western world, of course. Lee's response to my noting how he was born in 1927?: "Thanks for reminding me." Part of Nazir's inscrutable aura was his smoking of Indian cigarettes, known as beedies, with their exotically sweet aroma. He once hinted to me that he would enjoy smoking some pot, wrongfully guessing that I might have any access or interest in marijuana. On one occasion in New York City, perhaps regrettably because he is among other things an authentic mystic, I turned down an invitation to light up with Konitz while listening to his newly released and sublime Jobim Collection album, entirely comprised of duets with jazz pianist Peggy Stern. The tables of student and teacher were temporarily reversed when Nazir excitedly asked if I might make a meruvina realization of a music composition of his from years ago. I was glad to do so, of course, and curious to hear the result, but perhaps because Nazir's piece was originally intended for live musicians, the rendering proved unsatisfactory. Nazir did become unsettled upon hearing of something strange I had imagined seeing while housesitting. Forgoing the guest bedroom, which was poorly heated, I had taken to sleeping on the impressive futon in the living room, embellished with woven arabesques from India. One evening, in the dead of night, I became stuck in the state between dreaming and wakefulness, and imagined opening my eyes to see with absolute clarity a benevolent middle-aged man in Indian dress walking towards the grand piano, as if to play it. Then, surprised by my presence and stare - he abruptly stopped and stared back with extreme astonishment because there wasn't supposed to be anyone in the living room at that hour, as if his visitation was an ordinary ritual - the figure vanished. Not wishing a repeat performance of the dream, which unnerved me, I moved into the guest bedroom for the duration of my stay. It may have actually been a friend of Nazir who had the house key to play the piano but did not know that someone else was living there during the India visitation. A few days after the sleeping incident, I was studying the many interesting paintings hanging throughout the home when I recognized one of the portraits, hung in a previously unnoticed spot, as being the man I had seen in my dream, but with a beard! After Nazir returned from India, I inquired about the portrait, and related my dream about that person sauntering across the living room. After informing me that the portrait was of his grandfather, and giving my surprising story some thought, Nazir concluded that my dream didn't make any sense because his grandfather would never shave his beard, and had never played the piano. Uncharacteristically, because I always compose at a desk, I did write the theme for Scarlet Dawn while improvising at the Nazir's winsome piano, the title from a book of Vidyapati poems translated by Bhattacharya from the overflowing shelves. The scarlet dawn During my stay, I spent hours extemporizing upon various ragas and such at all hours, enjoying this more traditional approach to music. From Hills of Snow from the CHINESE LEGEND ALBUM featuring a piano timbre with tanpuras and percussion, inspired by Raga Bilaskhani Todi, made a special impression upon guests visiting from India when it was played at Nazir's house during one of the Friday night parties. Nazir had lived as a child in a mansion on the Arabian Sea in Bombay, his ancestors having converted to Islam from Hinduism many years earlier, making their fortune in the timber trade. However, the government seized their home and six acre property, worth billions today, after India’s independence from Great Britain was proclaimed. Among his many entrancing stories, Nazir told how during a low point of his life, he was without any money left to even feed himself, including his first wife and child. Despondent, he went for a rambling walk on a snowy day, and slipped on some ice, stumbling and falling down a snowy hillside. When the rolling fall ended, fortuitously uninjured, Nazir felt something metallic against his hand, and, miraculously, there was a quarter underneath the snow, which he then used to purchase some rice for his family. From that moment on, fortune would prove to be much kinder to Nazir. Now, Nazir is gone, having passed away in 2009, and it’s not uncommon for me to miss his generous warmth and prodigious intelligence. Many of those Friday evenings were magical, as was he. Precious few have been so capable of elucidating for the uninitiated the majesty and enigmas of India's classical music. Bravo, Nazir! And thank you for everything. No doubt, you would be amused to hear that part of you is alive in me, making a modest, self-depreciating aside, but its true, of course, as it is for scores of others around the globe. - Michael Robinson Longhi, January 2015, Kula, Maui

© 2015 Michael Robinson All rights reserved

Michael Robinson Longhi is a Los Angeles-based composer, pianist, and musicologist. His over 200 albums include over 150 albums for meruvina and over 50 albums of piano improvisations. He has performed and lectured at various American churches, universities, colleges, NPR, Pacifica, college, and community radio stations, high schools, elementary schools and community centers including all over the world online.

|